By Jason Baird

In these days, given the dominance of semi-auto pistols, why would anyone want to shoot (much less buy) a revolver? Semi-auto handguns have evolved from relatively unreliable pistols, unable to handle anything but military ball ammunition, to reliable sidearms that shoot most ammo and have large magazine capacities. Revolvers, on the other hand, have been shunted off to the sidelines because of their limited ammo capacities and concealment difficulty; both handicaps are because a revolver’s cylinder is its magazine, so the more cartridges it can carry, the larger the cylinder diameter. I could go on for quite a bit of article space citing the advantages of semi-autos over revolvers, but I’ll cut to the chase.

I’ve wanted a Smith & Wesson Performance Center 7-shot Model 586 L-Comp since I first saw one, because something about the way it looked grabbed me – I’ve always been a “revolver guy.” I own a similar Performance Center 6-shot Model 66 F-Comp that I carried with me constantly until Smith stopped building them. At that point, I knew if I lost the gun, I wouldn’t be able to easily replace it. I hated to do it, but switched to a semi-auto for concealed carry and put the 66 in our gun safe to stay except for fun trips to the range.

Smith & Wesson Performance Center 7-Shot Model 586 L-Comp

So, when S&W offered the compensated 7-shot Model 586 .357 Magnum revolver, I knew I’d have to get one eventually. The 586 is built on what Smith calls an L frame, which was supposed to be a little larger and heavier than the K framed 66 F-Comp, but both have 3-inch compensated barrels. More on the size and weight issues later, but I was surprised when I measured and weighed one against the other.

What’s the big deal about these revolvers? It’s an intangible thing for me. The first handgun I fired was a .22 caliber Colt revolver, but I was on the Air Force Academy pistol team in the mid-1970s and I put tens of thousands of rounds through S&W Model 41 .22 cal semi-autos (very fine target pistols). Therefore, it wasn’t a case of favoring the type with which I was most familiar. No, I think it relates back to an impulse purchase I made in 1977 – the first handgun that was mine. It was a beautifully crafted, blued S&W Model 19 Combat Magnum .357 Mag. Even though it only held 6 rounds and I had to reload the cylinder quite a lot while shooting, I was still able to use it to beat police officers with their new “wonder nine” high-capacity semi-auto pistols in local matches in the mid-1980s. I’d plug soft-shooting .38 Special target loads into my gun, while my opponents had to deal with the snappy recoil of 9 mm police ammo and frequent gun stoppages. Of course, semis and their magazines and ammo have improved significantly since then, so the competition results would go favorably in their direction in similar matches nowadays. Nevertheless, my love of revolvers was firmly cemented.

586 L-Comp versus 66 F-Comp

Comparison view 66 top v 586

I started comparing my 586 to my old 66. They are very close in form and size; each has a single compensator slot and expansion chamber cut into the barrel immediately in front of the front sight. One difference that presents itself immediately is that the 586 has a dull blue-black finish, where my 66 has a matte stainless finish. Upon closer examination, I noticed that the 586 has a small tritium vial inserted in the front sight so that in low light there is a dimly glowing spot where the center of the front sight would be if I could see it. The 66 has no night sights; it has an orange insert in its slightly wider front sight. The 586’s underlug goes all the way to the end of the barrel, but the 66’s is cut at an angle sloping away from the barrel’s end. Another different feature of the 586 is its ability to use the included 7-shot moon clips, or not, depending on the shooter’s preference for loading cartridges in to its cylinder, whereas the 66 does not use moon clips. One may also purchase speed loaders that work with the 586, but be sure to buy the 7-shot version instead of the one that only holds six rounds.

Comparison view 586 left v 66 right

On my kitchen scale, the 586, fully loaded with seven rounds in a moon clip, outweighs the fully loaded 66 (six rounds of the same ammo) by only two ounces. The 7-shot cylinder of the 586 is slightly more than one-tenth inch larger in diameter than the cylinder of the 6-shot 66, with all other dimensions nearly identical from one gun to the other. This surprised me, since the 586’s L frame is supposed to be more robust than the K frame of the 66.

I had difficulty finding holsters listed for the 586, having to return two holsters after purchase because the gun’s cylinder wouldn’t fit into the molded polymer. There was no way when ordering the holsters to specify the 3-inch barreled, 7-shot, 586 L-Comp versus a standard Model 586 6-shot version, and the two that I tried were obviously intended for the 6-shot gun. A MaxSlide outside the waistband holster I ordered from CrossBreed did fit the 7-shot gun because the company specifically listed the 586 L-Comp 7-shot gun for that holster. I didn’t try ordering other holsters that were made-to-order for the gun, as those companies said up front there would be a minimum of 8-to-12 weeks waiting before they would begin working on them. This shows why one should also shop for holsters when shopping for a gun if the gun is to be carried. My Galco leather pancake holster for the 66 fit the 586, likely because I have carried that holster so much that it doesn’t care about the additional tenth of an inch cylinder diameter.

According to my electronic trigger pull scale, the 66’s single-action pull was slightly less than the 586’s: 4 pounds 1.5 ounces versus 4 pounds 12 ounces (averaged over five pulls, each). Each gun’s double-action pull exceeded my scale’s maximum, 11 pounds, but the 66’s feel lighter to me than the 586’s. This isn’t unreasonable, given that I’ve put several thousand rounds through the 66 and only about 500 through the 586. Each gun had a discernable double-action pre-break point, and each gun’s double-action pull was smooth and consistent.

Shooting the 586

I shot the 586 L-Comp from a rest on my range bench at bullseye targets 15 meters away. For my purposes, 15 meters is a good target range when I’m testing short-barreled handguns because they lend themselves to concealed carry and use at social distances (from in-contact to about as far as a conversation can be easily held). In addition, a short-barreled gun has a short sight radius (the distance from the rear sight to the front sight) that makes it difficult to shoot accurately at long distance. If I’m out and about on my ranch and not expecting trouble I carry longer-barreled large-caliber guns in larger belt holsters so that I can easily engage targets at longer ranges; I don’t have to bother to conceal the guns.

I tested ammunition from several companies, since guns tend to have favorites among cartridge loadings. I shot five shot groups using .38 Special ammo from Aguila and Remington, .38 Special +P ammo from Remington, and .357 Magnum ammo from Aguila, Remington, Barnes, and Hornady. I tested each one with and without moon clips to see if the clips made any difference in accuracy; information about my testing, the ammunition, and the results are in sidebars.

Not surprisingly, the way I shot the gun favored one of the .38 Special loads. Considering average overall numbers, the Aguila .38 was number one for accuracy without a moon clip, and ranked second behind one of the .357 loads when clipped into a moon clip. I was surprised, however, how small the spread was between the best and worst group averages for all the ammunition I tested, and that the moon clips had a slight negative effect on my accuracy averages.

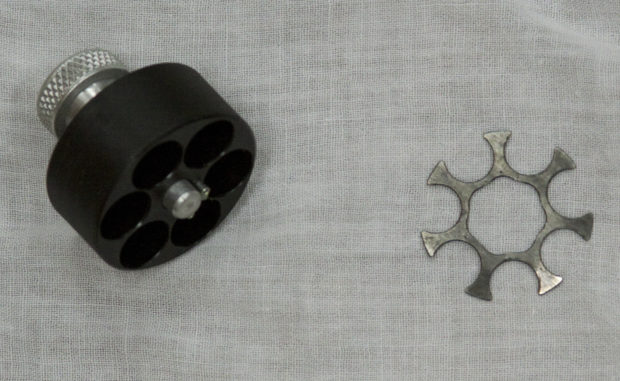

Loaded speed loader left versus moon clip right

I also tested the effect of the compensator on how quickly I could get the gun back on target by shooting timed pairs at 8-inch diameter steel targets 15 meters downrange. Starting from the low ready position, I used Remington .38 Special and .357 Magnum lead-projectile ammo in the 586 in a speed comparison to my old Model 19 with the same ammo. My averages were faster using the compensated gun in each case, .38 Special versus .38 Special and .357 Magnum versus .357 Magnum; in fact, my .357 averages with the 586 were better than both the .38 and the .357 averages with the 19.

The Finale

The Model 586 did not disappoint me; I like the way it looks, balances, feels, and shoots. So, I am adding it to my stable of revolvers and concealed carry guns. I’m happy that I can save my old 66 L-Comp for occasional trips to the range for fun shoots, while keeping its near-twin concealed on my hip for trips off the ranch. Suggested retail is $1,208.00.

Ammunition Tested

.38 Special

- Aguila 138 grain Full Metal Jacket

- Remington 158 grain Lead Round Nose

.38 Special + P

- Remington 125 grain Semi-Jacketed Hollow Point

.357 Magnum

- Aguila 158 grain Semi-Jacketed Soft Point

- Barnes 125 grain TACXPD Hollow Point

- Barnes 140 grain VOR-TX XPB Hollow Point

- Hornady 125 grain Critical Defense FTX Polymer Tip

- Remington 158 grain Lead Semi-Wadcutter

Moon Clips and Speed Loaders

A speed loader releases its cartridges into the gun’s cylinder when shooter twists the knob at the top; a loaded moon clip is simply inserted into the gun’s cylinder. Moon clips will fit into speed loader pouches. Loading and unloading a revolver using moon clips is faster for some shooters and the empty cases are held together after the gun is unloaded. Moon clips hold their cartridges in place by spring tension in the undercut ahead of each cartridge’s rim. There is no industry standard that I could find for the undercut dimensions (in fact, an undercut is not currently required by the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute, or SAMMI, as a part of their Voluntary Standards) or for the moon clips themselves, so be aware that some cartridges may not fit into some moon clips. I had that problem with the Hornady cartridges, and was only able to test one 5-round group using a moon clip. In addition, loading and unloading cartridges from moon clips is difficult (but not impossible) without special loading and unloading tools.

Speed Loader on the left, Moon Clip on the right

Dr. Jason Baird is a graduate of the United States Air Force Academy and Air Force Institute of Technology. He has a Ph.D. with a field of study in Mining Engineering and Explosives Engineering. Dr. Baird is currently the president of Loki Incorporated, a firm specializing in engineering services to the explosives, propellant, and pyrotechnics industry.