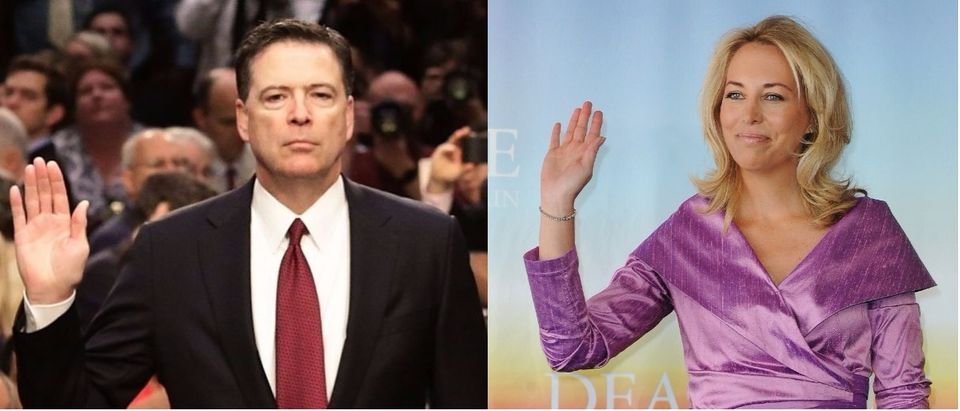

The recent kerfuffle over the dueling Steele dossier memos revealed a significant lacuna in Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s Russiagate investigation: There appears to have been no probable crime causing conflict of interest, the prerequisite for his appointment. This should come as no surprise to anyone who has followed James Comey’s career as of late.

It was Comey who, in 2004, as the Deputy Attorney General (Attorney General John Ashcroft had recused himself) appointed Special Counsel Patrick Fitzgerald to investigate the crime of publicly identifying, or “outing,” CIA Agent Valerie Plame, seemingly a violation of the Intelligence Identities Protection Act (IIPA) (U.S.C. §793). The statute makes it a crime to reveal the identity of any intelligence agent who has acted under cover in a foreign land in the preceding five years.

The subsequent “Plamegate” indictment caused a rush of excitement as untold scores of anti-Bush scribes wrote about the trial of Lewis “Scooter” Libby, a top aide to Vice President Dick Cheney. A movie starring Naomi Watts and Sean Penn dramatized what was portrayed as a conspiracy to punish Plame’s husband for debunking Saddam Hussein’s pursuit in Niger of “yellow cake” uranium, a claimed pretext for war. Fitzgerald’s dragnet narrowly missed presidential adviser Karl Rove.

Comey benefitted greatly from the political drama. He exacted revenge against Cheney and Libby, who had fought him and Mueller at Ashcroft’s bedside over extension of a controversial FISA provision. It gave Fitzgerald, the godfather of Comey’s child, a great gig. And it burnished Comey’s “good Republican” reputation among Democrats.

There were, however, a few problems with Comey’s referral. One was that the FBI already knew who had outed Plame to columnist Robert Novak. It was Richard Armitage, Deputy to Secretary of State Colin Powell.

Another problem was — as Comey knew, but the public did not — that, while there would have been a conflict if a crime were shown, there was absolutely no crime to investigate, because IIPA arguably did not apply to a person with Plame’s status. The public did not learn of this failing until a brief, seeming aside in Fitzgerald’s announcement of Libby’s indictment. But the noble Comey was nonetheless covered in glory by Libby’s indictment, as no major media outlet took him to task.

Taking a break from politically-motivated charges, Comey, shredding the FBI’s image of political independence, in 2016 effected a politically-motivated exoneration of his presumed future boss, presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, on charges of gross negligence in the handling of classified information.

Months later, as Comey pursued a trumped-up “Russian collusion” investigation, his unexpected new boss, the inexperienced Donald Trump, wanted a public exoneration, much as Comey had done earlier for Hillary Clinton. Retreating to what should have been his proper stance regarding Clinton, Comey refused to provide such an exoneration, and he was fired. He then proudly and publicly inveigled Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein to appoint a special counsel, whereupon Rosenstein appointed the unimpeachable Robert Mueller.

Once again, as in Plamegate, there was no probable crime causing a conflict, and therefore no legitimate basis for the appointment. Rosenstein can be excused, because he was relying on a probable criminal conflict on the Russian investigation… pursued by Comey!

The investigation was started to at least some extent on the flimsy basis of a casual, drunken comment by George Papadopoulos, but even if these comments were substantial, they only gave rise to a counterintelligence investigation, not a criminal probe.

So if “a criminal investigation… is warranted” which would “present a conflict” (28 CFR 600.1), it must be found in the “salacious and unverified” (Comey’s words) Steele dossier. If there is no reliable evidence of a conflict-causing crime in that dossier, there was no valid basis under statute to appoint Mueller. So if the Steele dossier is suspect, and the result of largely partisan smears, laundered using a British spy as a cutout, we are left with a Kafkaesque criminal investigation, one with criminal interference by Russians, but none by the Trump Administration.

A foreseeable consequence of a crimeless criminal investigations, as in a Kafka novel, is that a subject of questioning will likely stumble into false denials. Libby, erroneously thinking that a leak of Plame’s name was a crime, denied it. Years later, Michael Flynn, rattled by Comey’s apparent embrace of the vestigial, never-used Logan Act, denied speaking about sanctions with a Russian ambassador. It would surprise no one if Donald Trump Jr., thinking he needed to forestall a charge of “Russian collusion,” dissembled about his meeting with Russians, perhaps with his father’s help. And there may also be tangential financial crimes not going to “Russian collusion.”

All of this gets us back to Comey. He is experienced and wily enough to know that “process” crimes (i.e., lying and obstruction) are inevitable in almost every investigation, albeit rarely pursued in pedestrian cases. But he also knew that in Russiagate, as in Plamegate, process crimes or tangential wrongs would be the only scalps available for Special Counsel who can be criticized only if he comes up empty.

Comey knew that process crime convictions in Russiagate will only enhance his anti-Trump reputation. This attempted replay of the Libby fiasco, however, won’t make it through the gauntlet this time, in light of the phony dossier. There are too many commonsense citizens who can smell phoniness a mile away, given enough information. They will not sit still, in short, for a Presidential prosecution flowing out of a partisan Steele dossier, unless President Trump provably colluded with Russian criminals.

So Comey put the impressive Mueller in a bind. The special counsel was put under pressure to produce indictments, but knows he had “no there there” regarding substantive electoral interference crimes of the White House.

Mueller has brilliantly ttaken the first step out of his dilemma by indicting 13 Russians, but no Americans. He will also continue to search for process and tangential crime against any White House officials, as he did with Flynn and Manafort. But if he does not have the real “Russian collusion” goods on the sitting president, the disciplined Mueller should exercise the better part of his Marine valor: discretion.

So for the sake of our country, we should all hope that Bob Mueller does not base a sensational prosecution, and create a true crisis, on another of Comey’s crimeless cases.

John D. O’Connor is the San Francisco attorney who represented W. Mark Felt during his revelation as Deep Throat in 2005. O’Connor is the co-author of “A G-Man’s Life: The FBI, Being ‘Deep Throat,’ and the Struggle for Honor in Washington” and is a producer of “Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House” (2017), written and directed by Peter Landesman.

The views and opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of The Daily Caller.