- Chief of Police points to less stringent penalties emboldening criminals

- Tough gun laws said to be ineffective with D.C.’s shared border with Va.

- Easy access to guns means that petty disputes end up as homicides

- High capacity magazines result in more lethal shootings

WASHINGTON — Zyair Bradley was 20 years old. He loved football and boxing, music, dancing and playing jokes on people. He had a job and “a million friends.” He was a son, a protective big brother and his mother’s “beautiful angel.” He was also one of 18 people to have been murdered in the District of Columbia just this month.

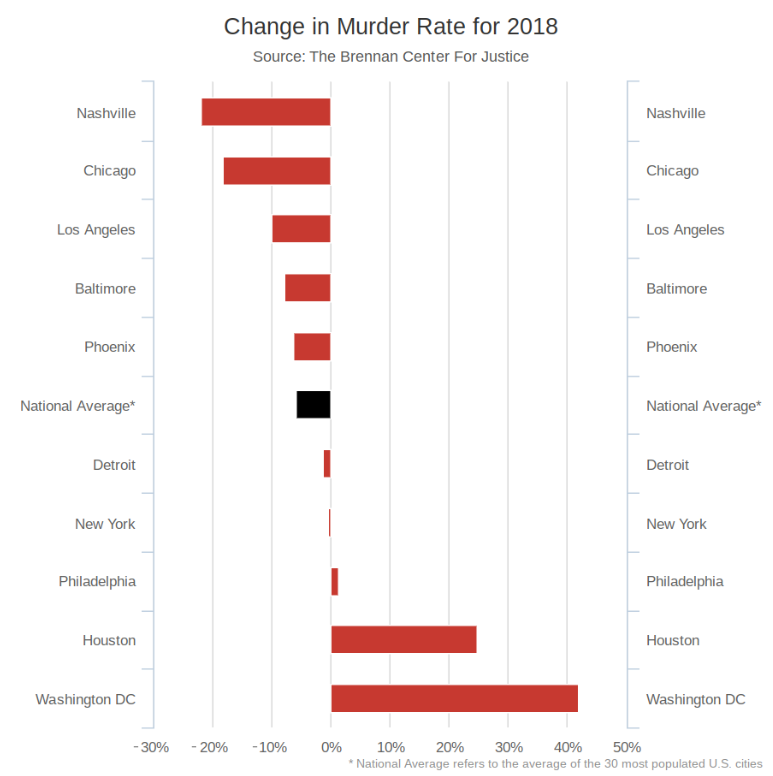

As homicides across the country’s most populated cities declined overall in 2018, Washington, D.C. saw an increase of almost 42 percent in its murder rate, which experts say will continue to trend upwards in 2019. The D.C. Chief of Police warned that easing penalties would make the District less safe.

“Repeat offenders who have committed gun crimes will be back on the street sooner,” wrote Chief Peter Newsham in an editorial that ran in The Washington Post last summer. “Less-stringent penalties embolden criminals, demoralize law enforcement and enable violent offenders to return more quickly to terrorizing the very communities who are calling out to the government for help.”

For law enforcement officers, it’s frustrating. For mothers like India Bradley, it’s devastating.

“I had to sign my baby’s death papers,” Bradley said. Alexis Washington, who was killed along with Zyair, left behind a 3-year-old son. “That little boy — as I’ve lost a son, he’s lost a mother. I pray for justice daily. We need answers.”

Police stand behind a police line near the White House as a small group of Alt-right members hold a rally in Washington, DC, on January 5, 2019 (Photo by Andrew CABALLERO-REYNOLDS / AFP)

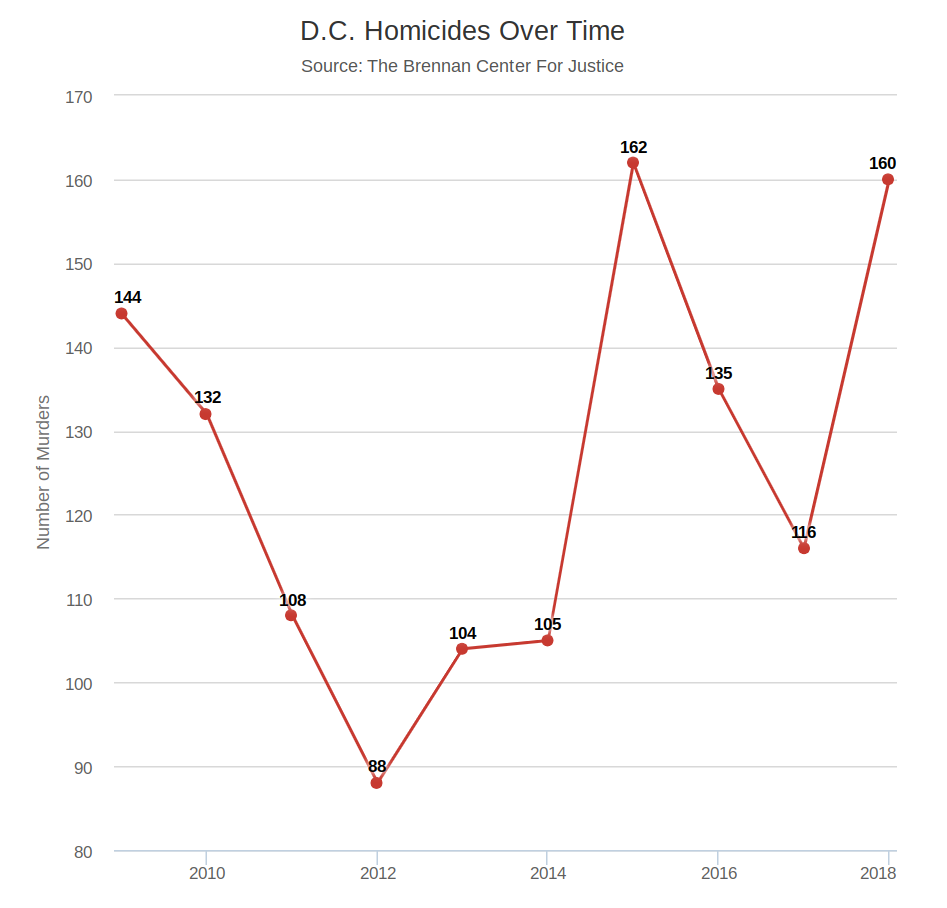

The Brennan Center for Justice reported 116 homicides in the District in 2017 and 165 in 2018. In other cities like Baltimore, Detroit and Chicago, homicides fell.

“In context, it takes us back to where we were in DC a couple years ago,” said Ames C. Grawert, senior counsel in the justice program at The Brennan Center.

By Helen Lyons/Contributor for The Daily Caller

Robert Contee, the assistant chief of the Investigative Services Bureau at the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) in Washington, D.C., pointed to a few central issues at the heart of the homicide spike.

One, Contee says, is access to illegal firearms.

“We have some of the toughest gun laws in the country,” Contee pointed out. The District tried to ban handguns entirely until the Supreme Court ruled the measure unconstitutional in 2008. But D.C. is only a short metro ride from Virginia, which received a ‘D’ grade on the Gun Law Scorecard, a project of Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. (RELATED: DC Mayor Vetoes Metro Fare Evasion Decriminalization)

Even still, some of the illegal firearms recovered from D.C. homicides come from as far as North Carolina. (RELATED: Eliminating DC’s Handgun Ban Had No Effect On Homicides)

“When you’re talking about the effect of gun control and violent crime rates, you can’t just talk about the gun laws in a city,” said Grawert. “You have to talk about the gun laws in the surrounding places.”

The District’s proximity to Virginia and Maryland — which send thousands of commuters in and out of D.C. every day — complicates any policies it enacts.

Marijuana was decriminalized in Maryland and the District, but remains illegal in Virginia, for example. This means that if you’re a Maryland resident who takes the Metro into D.C. to more easily buy recreational pot, then continues on into Virginia for work, you can be stopped and charged with possession once you arrive. (RELATED: Legal Weed Operations Are Sending Their Cash To One Bank In Maryland)

The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) that operates the metro system for the region is also the subject of inter-jurisdictional squabbles. In recent debates regarding the decriminalization of fare evasion proposed by the D.C. City Council, opponents argued that it would be Maryland and Virginia left to foot the bill when it comes to lost revenue, despite the fact that the overwhelming majority of fare evasion takes place at stations inside the District.

As for gun control, Grawert says, its effectiveness in a given place generally depends on the laws of its neighbors.

“New York City and Chicago are both places with extremely strict gun laws, but guns pour and pour into Illinois,” said Grawert. “Most Illinois crime guns come from Indiana, which is a state with really lax gun laws. It’s not that gun control doesn’t work, it’s that if you place a strict gun law city in the middle of a lax gun law region, you’re going to get very different results.”

Another factor contributing towards the rise in D.C. homicides is the increase in the lethality of the weapons used in shootings.

“There was a time when you may have had seven or eight gunshots fired on your average homicide,” said Assistant Chief Contee, who joined MPD as a cadet in 1989 and recalled a time when officers responded to multiple homicides in a single shift. “Now we’re seeing upwards of 50, sometimes 60 shots fired. When you have someone firing a firearm 50 or 60 times, the likelihood of getting hit is much higher.”

The results are often tragic, like when a shooting in southeast D.C. last October claimed the life of a 10-year-old girl on her way to visit an ice cream truck nearby.

It’s not just gun homicides, either. A woman was stabbed to death in Logan Circle in a seemingly unprovoked attack last September. Wendy Martinez was jogging on a well-lit street in what’s considered to be a safe neighborhood. She was 35 and newly engaged.

When India Bradley thinks about the senselessness of her son’s murder, she considers the loved ones left behind.

“Zyair has a two year old brother,” says Bradley. “I wonder if he’ll remember him.”

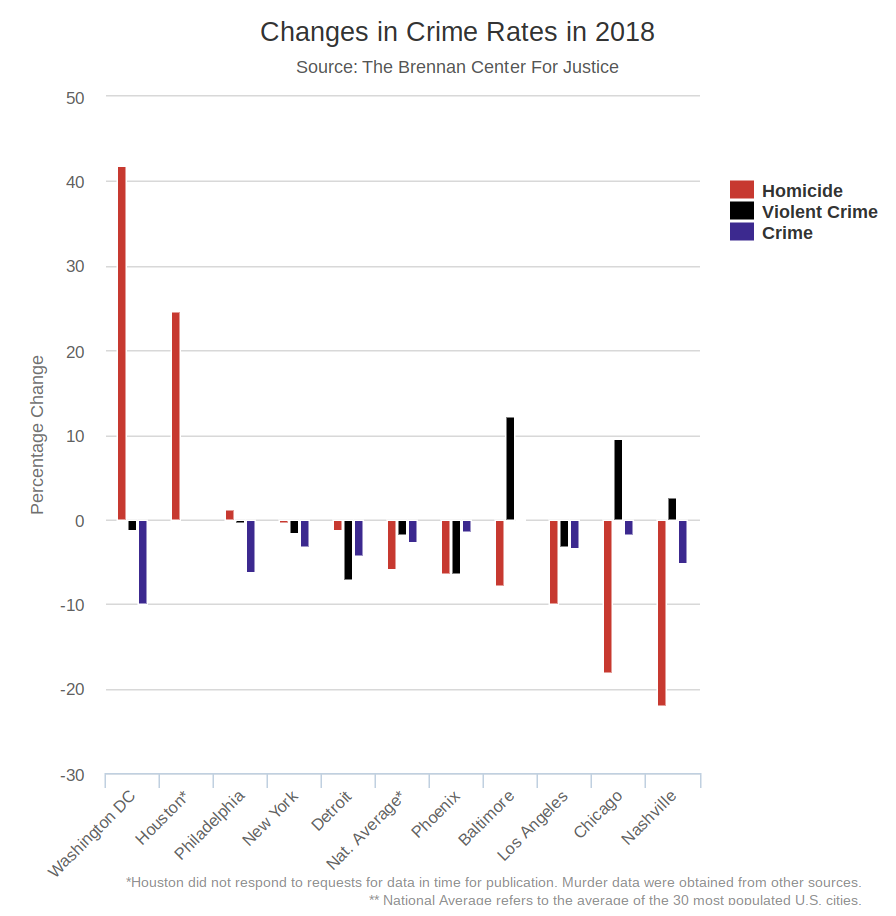

The Brennan Center reported that the 2018 murder rate in the 30 largest American cities was estimated to have declined by nearly six percent overall, in part because of large decreases in Chicago and San Francisco (18.1 percent and almost 27 percent, respectively).

Violent crime rates and overall crime rates also fell, even in those cities that saw increases in their homicide rates.

By Helen Lyons/Contributor for The Daily Caller

“In general, homicide rates have been declining significantly since 1990,” said Grawert. “The national murder rate is around half of what it was in 1990, so the general trend for cities lately has been towards greater safety. It’s not always even, it’s not always as big a drop as one would like, but the general trend is that cities are getting safer over all.”

But D.C. is an outlier. The Brennan Center predicts its murder rate will climb 39.5 percent this year (Houston is another exception, with a 22.6 percent increase expected for 2019).

By Helen Lyons/Contributor for The Daily Caller

While previous spikes (like the one in 2015) had clearer explanations, 2018 left many of the experts The Daily Caller spoke with baffled, for the most part.

“D.C. stood out to us in terms of a few key aspects — it’s generally a poorer city than a lot of the others on our list, more problems with economic inequality — those were all common traits with cities that experienced upticks in 2015,” said Grawert. “The same can’t be said of 2018.”

“We’re doing everything that’s humanly possible that we can do as a government to provide people with options other than engaging in criminal behavior,” said Contee.

In addition to easy gun access and more lethal weapons in the hands of criminals, he points to weak penalties for violent crime to potentially help explain why the District saw such a spike in the midst of national declines.

“We have a lot of people being arrested for gun crimes but they’re not doing any real time. That’s a problem when you’ve seen a guy being arrested five, six times. Violent offenders repeatedly come through the system,” Contee said. “The biggest frustration that we have here in the agency is when you see a person who has committed multiple violent offenses and there not being any real penalty with the crime.”

Whether it’s a shooting or simply a felon caught with an illegal firearm, Contee says that after going to trial and pleading guilty, there’s “no real penalty.”

The Chief of Police pointed to the District of Columbia Sentencing Commission’s guidelines as the reason for that, but those are only suggestions for judges, not requirements like mandatory minimums. The Sentencing Commission told The Daily Caller that the mandatory minimums some feel are too lax originate in the D.C. City Council.

“It’s something that should happen in the court,” says Contee, but it doesn’t. “If a guy walks away with six months or time served, that’s not really helping.”

Not everyone agrees that tougher penalties are the solution.

“There’s not a great argument to be made that harsher sentencing laws are the silver bullet to crime,” said Grawert. “We [wrote] a report that looked at the relation between incarceration and the decline of crime between 1990 and 2015. It’s easy to look at that correlation and say ‘incarceration led to a decrease in crime,’ but that’s not actually the case. The growth in incarceration in that time did very little to affect that decrease in crime.”

Yet when it comes to penalties for violent crime, just as with gun laws, Contee points to New York and their apparently harsher punishments.

“When people talk about gun crimes I like to look at New York,” he said. “There are consequences in New York if a person is caught with a firearm. If that’s not the case with D.C., if there’s no accountability, you see violent crime go up.”

Contee acknowledged that mandatory minimums can often lead to an overly punitive justice system.

“We do have an issue with ‘lock em up, lock em up, lock em up,’ but you look at New York City and you look at the number of homicides and the penalties, it’s different. If there’s no accountability, you see violent crime go up,” he said. “Officers are out here putting their lives on the line every day. That’s their job, that’s what they do. With D.C., at the end of the day, there’s concern about people not being held accountable.”

While illegal gun trafficking, more powerful weapons and laxer penalties can generally be pinned down to data points or conceptualized with infographics, there’s one last observation from D.C. police that’s harder to put into any neat visualization.

“The time when we had 400 murders happening a year, [they] were over drug disputes, turf disputes,” said Contee. “The thing that’s different now is that the majority of the homicides are the result of some petty dispute.”

Whether it’s giving “the wrong look at a gas station” or a simple argument, motives have shifted over the years.

“It’s not domestic. It’s not robbery. It’s petty dispute and that is a huge difference between now and 1989 when I came to the force,” Contee said.

Data cannot always completely account for human nature.

“Over the last six or seven years we’ve had some of the most historic lows in our agency for homicide and violent crime,” said Contee. “But one homicide, one violent crime, is too many. Whether it’s one or 20, it’s too many.”

As police continue to search for those responsible for the most recent shootings of Alexis Washington and Zyair Bradley, families of victims— including Zyair’s mother— remain without answers.

“When all of you go back to your regular lives, I’ll still be going through it,” said India Bradley. “All lives matter, when they’re black or whatever nationality. All lives matter, but now I’m speaking to you as a mother. My son’s life mattered then and it matters now and it will matter tomorrow and the day after. I miss my baby.”

This time last year, the District had seen seven homicides. As of publication, there have already been 18.